The price is wrong: Financial markets aren't very informative

Limits to arbitrage mean that prices rarely reflect the fundamentals. How well do markets work, really?

In certain corners of economics, there’s a belief that the market price for a financial asset is always the same as the fundamental value of that asset. If the price were ever too low relative to fundamental information, some rational and well-informed investor would buy the asset. Similarly, if the price were ever too high, rational investors would sell it. Over time, the market price will come to reflect all fundamental information about the asset, as informed investors arbitrage away price discrepancies driven by the uninformed investors.

This idea, that markets are efficient at incorporating information, is the intellectual basis for the trillion dollar passive investing industry (and for the idea that a free-market economy can allocate goods better than a centrally planned one). In practice, few would say that markets are entirely efficient, but there is a general consensus that markets are mostly efficient. And since markets are perceived to be efficient, investors, policy-makers, and analysts pay close attention to price changes, which should reflect information changes. But certain structural facts about financial markets raise questions about the information content of prices, and, more broadly, how well markets actually work.

It’s easy to take advantage of an underpriced financial asset. If a bond is cheap relative to its expected interest payments, or if a stock is cheap relative to its expected dividends, an investor can just buy the asset. But there is no obvious way to turn an overpriced asset (that you don’t already own) into its fundamental value1. If a stock is trading at $20, and an investor determines its fundamental value is $10, the only way to capture this discrepancy is by selling the stock short and hoping that other traders will eventually drive the price down to its fundamental value. In textbooks, this isn’t an issue, as the collective short selling by rational investors will eventually drive prices to their appropriate level. But in the real world, where short sellers face serious constraints, this logic begins to fall apart.

The most obvious constraint to short selling is collateral. If you short a stock, you have to put up some cash as collateral. If the stock continues to rise, you either have to stump up more collateral, or your broker will liquidate your position at a loss. Similarly, if you enter a marked-to-market trade (like a futures contract or some sort of total return swap with a bank), you’ll have to post additional collateral to satisfy margin requirements if the trade goes against you. Since no investor has access to limitless amounts of liquidity, short sellers face the risk of being forced to exit their positions at a loss in the short-term, even if their trade would have paid off in the long-term. Additionally, if a trader is acting on behalf of a financier who doesn’t really understand the intricacies of the trader’s market, they might threaten to pull funding as losses accumulate2.

Informed investors shorting an overpriced stock essentially face the risk that they’ll be blown out of their position by speculators unconstrained by valuations. If you’re a speculator buying stock because you expect other speculators to buy as as well, then the nominal level of the stock compared to some fundamental value doesn’t matter at all. For traders betting on a 10% rise in a stock, it’s not important whether the initial price was $1, $10, or $100. Since only deviations from the current price matter, a fundamentally overpriced stock can easily become more overpriced through speculative trading.

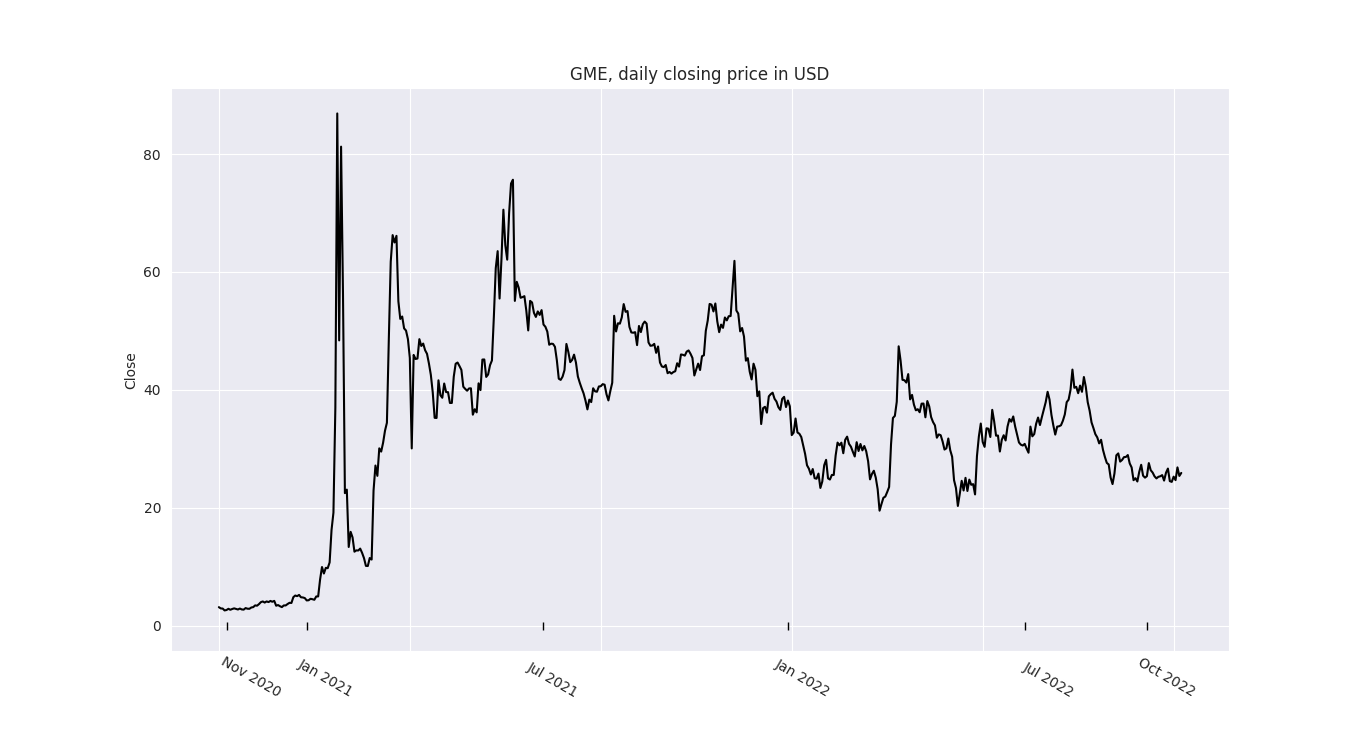

This seems to be the basic story of meme stocks, especially GameStop. Traders (particularly retail ones, the quintessential ‘uninformed’ traders) piled into the shares because they expected the ‘meme-iness’ of the situation to pull in other traders and drive the price even higher. No one bought GameStop at $80 because of its cash flows. Short sellers were unwilling to take the other side of the trade, as the volatility made collateralizing the short position extremely expensive and risky. Some short selling hedge funds blew up, much to the delight of GameStop fans.

The idea that a market price can be ‘wrong’ because it’s too risky to take a short position has important consequences not just for investors, but also policymakers. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the price of wheat futures spiked by over 40% on the narrative that Russia and Ukraine represented irreplaceable suppliers to global wheat markets. Less than four months later, prices had fallen to pre-invasion level. Policy decisions were made based on the toxic combination of a belief in the informative power of prices and a price driven mostly by speculation. Similarly, European natural gas futures have fallen to pre-invasion levels after a brutal rise of over 200%. Because there are limits to arbitrage, traders who understood that rerouted liquefied natural gas from Asia could satiate European demand (and that storage was pretty full anyway) were unwilling to take short positions.

The aesthetic ideal of financial markets is to enable price discovery that lets capital flow to its most effective uses. If the current structure of finance means that fundamental value is a floor on prices, but not a ceiling, then modern finance is pretty far from that ideal. Limited arbitrage implies that prices are overly influenced by speculative traders with no view as to the productive capacity of the underlying investment. This raises some discussion questions about how markets could be made to work better, including:

1. Is it too easy to trade? If you want to bet that the price of wicker chairs will rise because other speculators will start buying wicker chairs, you probably have to go to a furniture store, transport the chairs to a storage facility, store them for weeks, then find another speculator to sell them to. Probably not worth the effort. But if you want to bet that the stock price of a wicker chair manufacturer will rise for similar speculative reasons, it takes you two clicks on a brokerage account3. If it’s harder to trade, will only fundamental investors trade?

2. What is the actual impact of the rise of passive investing? Passive investing, which essentially reduces to buying the S&P 500 regardless of price, is not exactly speculative, but it does have some speculative characteristics. This is especially true if you assume that other investors will tend toward passive investing over time, which will drive prices higher. Usually, arguments about the distortionary nature of passive investing are waved away with the idea that as long as some small subset of investors are rational and focused on fundamentals, they will keep prices anchored. But limits to arbitrage mean this might not be true.

Prior to the 1990s, it would have been economic sacrilege to question the strict efficient market hypothesis. Even with the rise of behavioral finance and the study of heuristics and biases, the idea that markets are mostly efficient still seemed plausible. But the practical limits of arbitrage, and the existence of pure bubbles like Bitcoin, cast doubt on even this belief. Market prices still contain information, but probably not as much information as we thought.

1: This differs from the market for physical goods, where a supplier without initial inventory can obtain more goods (through manufacturing, or refining, or mining, etc.) and then sell those goods into the market and take advantage of the higher price. An interesting case is a company with an inflated stock price. The company is the only one who can authorize and sell new shares. Hertz tried to issue shares when the company was trading at meme prices, but the SEC didn't let them. Even in futures markets, where physical goods and financial markets intersect, suppliers of the commodity cannot always cool a bubble by selling into the market. Nickel producers facing margin calls were part of the LME turmoil this March. Even if a nickel producer is theoretically hedged by its physical supply, they still have to provide the actual exchange with lots of financial collateral.

2: Yes, like this scene in The Big Short.

3: For a related reason, highly divisible assets probably contribute to speculation. If you can only buy integer amounts of Bitcoin, and Bitcoin is $20,000, then it's expensive to speculate. But if you can just buy fractional amounts, speculation is open to everyone. Fractional shares in retail brokerages have become more and more popular over the past five years. Similarly, stock splits to reduce share prices can encourage retail speculation in options (which for historical reasons are sold in minimum batches of 100 shares) which can push up stock prices (due to hedging activity by market makers). This is probably why Tesla has been splitting its stock over the past couple years.